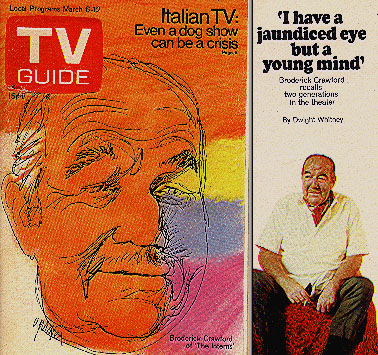

Broderick Crawford recalls two generations in the theater

by Dwight Whitney

|

We're sitting around shooting the early-morning breeze in Broderick Crawford's place, a garish South Vine Street motel with decor heavy on the Day-Glo orange. As usual Brod has been up since 6. As usual he is feeling no pain, and it is not even 9 o'clock in the morning.

Several empty beer cans line the coffee table. Another half-full one is poised for take-off in a hamlike hand. In the kitchen, next to the empties and the vitamin-B complex, stands a tumbler smelling suspiciously like vodka.

"Fuck with me and you're fucking with dynamite," roars this magnificently battered, enormously likable, lonely, beautiful bull of a man. "My mother always said be ready, so I start the night before. My father, who broke my nose the first time because I failed to call him 'sir,' told me, 'Son, in a bar or a theater, always look for the exit - and hold it down to beer when working. But when it's cocktail time stand back!'"

In one way or another all the things that matter to Crawford, the 59-year-old Academy Award-winning actor who made a fortune getting in and out of police cars in a musty old TV show called Highway Patrol, are present in this room: A just-started clown painting. Stanislavsky's "An Actor Prepares" next to a book on the comic art of W.C. Fields. An antique swagger stick from Yucatan, leopard and snake intricately carved into its ivory head, to remind him of his many other beloved antiques, now in storage. A note from his 19-year-old son, Kelly, which begins, "Dearest of All Fathers, If you have the unmitigated gall to wake me up at 6 A.M., you can at least

A line of empty vin rose bottles, the drink favored by the young, painstakingly arranged over the kitchen cabinets. The only thing missing is a copy of "Of Mice and Men."

The vin rose bottles, Brod says, symbolize his recognition of the Generation Gap. "The kids. I believe in 'em. They got a helluva beef. National Guard on campus! Kids bleeding in the streets! I have a jaundiced eye but a young mind. Of course, Kelly he uses me for a mail drop. Kim, he's married and lives in Florida - is me in a disaster area. If they weren't my sons they'd be the best friends I had." Pause. "But I'm their father, so once in a while I have to kick their asses.

"I got it figured. Now write this down, it's a prepared statement like Nixon. You live your life, I'll live mine. I'm too young for Medicare and too old for broads to care. I collect antiques. Why? Because they're beautiful. The prop men can see me coming. They know I'll steal anything with a mark on it.''

Some things in the room haunt him. tike the framed picture of his mother, Helen Broderick, wearing that fantastic pillbox and looking every inch the star of "Fifty Million Frenchmen," "The Band Wagon" and "As Thousands Cheer." The Fabulous Helen ruled Broadway of the '30s with her wit.

"Helen," George S. Kaufman said to her once during one of those rare times when the playwright was sweating out an unsuccessful play, "your slip is showing." "George," replied Helen, "your show is slipping."

Helen also ruled her only child, and even with his mother dead 12 years, it sometimes seems that when Brod drinks he is really drinking to her. When she sneezed, he put it in quotes. One of his most vivid memories is of his mother dusting off De Wolf Hopper, he of the many wives and the galvanic charm.

"She spotted him in a restaurant," Brod is recalling mistily. "My grandfather had worked for the great man in operetta, and she was determined to meet him. She said, "Excuse me, Mr. Hopper, but I'm Bill Broderick's daughter, and this is my son, Brod Crawford." He looked pained and said "Oh, that's nice. When you see Bill say hello for me". My mother froze. Then she snapped, 'You're going to see him first, so say hello for me, because he's been dead for 20 years!'"

|

|

Broderick Crawford and Helen Crawford Nice Girl, 1936. |

Brod was a long time convincing her he could act. Even after Ethel Barrymore had climbed four flights in 1935 to tell Helen's fledgling actor son how good he was in Noel Coward's "Point Valaine" with the Lunts, Helen was unconvinced. "She said it was better to be a plumber - he worked regular," Brod roars. It was she who took de-light in scuttling his girls by "making me laugh with her impressions of them." It was she who first read "Of Mice and Men" and decreed the role of Lennie the half-wit, "too difficult" for him to handle. When, despite every-thing, "Lennie" made him the toast of Broadway, it was Helen who sifted the offers.

"Ah, Mother," Brod is saying wistfully. "She was the most beautiful bleep God ever put on this earth."

Only once did he really come out on top in the battle of wits. At the height of his mother's fame he was sitting in Walter Huston's dressing room word came through that the mighty George M. was on his way up. Husten, nervous, tried unsuccessfully to shoo his young visitor out but was forced to introduce him. "This is Helen Broderick's son," he told Cohan. Cohan looked blank. "Helen who?" he said. "Helen Broderick." Cohan still looked blank. "Oh," he said. Brod sent his mother a wire: "Get in touch with George M. Cohan immediately. He admires your work. Love, Brod."

The man who squirmed most was Lester Crawford, Brod's feisty father. Things weren't so bad in the old days when he and Helen constituted the vaudeville team of "Crawford & Broderick, Songs, Dances, Funny Sayings." It was kind of act that opened with "Haven't I met you somewhere before?" and Lester was the kind of a guy who carried his 6-week-old son on-stage for the first time. (Brod made his formal debut at 7 running across the stage and yelling, "Tag, you're it!") Lester also wrote. "If it ain't Shakespeare," he used to say, "I'll rewrite it."

"My father was always telling himself no one was perfect, not even my mother," Brod is saying. "But she became a star and he became third man on the totem pole. He developed a deep resentment of me. I made it, he didn't. But he loved me and I'd do murder for him."

No question he identified with his father. "I am the old man," he cries. Still, Brod managed to hold his own, even against the great George Kaufman. Brod had been fascinated with Steinbeck's small tragic novel, "Of Mice and Men," and particularly with the character of Lennie, "a baby with the body of a gorilla who scared me and broke my heart." When he heard that Kaufman was directing it as a play, he went to read for the playwright.

"I'm a lousy reader," he recalls. "I don't see the words, I see the part. So instead I told him what I thought Lennie was about. I'd seen a Jackie Cooper movie once about a kid who wouldn't eat his oatmeal. That's how I wanted to play the - fucking idiot - like a petulant child who really hates the stuff. Kaufman was impressed as hell. He cast me."

Helen's boy opened in New York in 1937. "Not a sound at the final curtain," Brod remembers. "I thought I'd failed. Then the murmur then the cheers ..." "Beautiful, kid," his father said. "Well," said Helen, "I guess the business world will have to get along without you." Brod thought he had it made. One night he was goofing off. He picked the wrong night - Kaufman was in the theater and promptly sent him a telegram backstage: Am sitting in the back row. Wish you were here. George S. Kaufman.

|

|

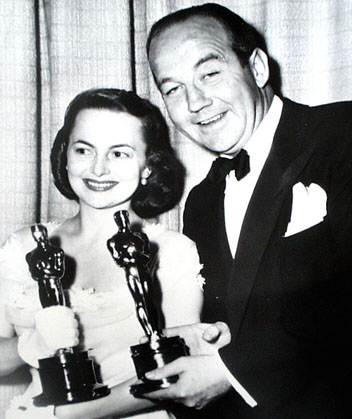

Oscar© for Best Actor in 1949 All the King's Men (with Olivia DeHavilland) Oscar© is copyrighted by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences |

|

| . |

|

|

publicity poster from

All the King's Men that hung in the Brown Derby |

In the end the movies got Brod - or, the movies got him in the end (with Brod it is never quite clear which). Somebody else (Lon Chaney Jr.) played Lennie in the 1939 film. Brod's films ran hot and cold, but he had the quality. No performance was completely uninteresting, even in the things like "Sin Town" or "Butch Minds the Baby." In 1949 he finally hooked onto a part he could feel in his gut - Willie Stark - the Southern politician of "All the King's Men." When he got his Oscar, who should be there to congratulate him but Ethel Barrymore. "See?" said Ethel, "I told you so."

His appetites were enormous. When he worked - he worked harder than anybody. When he played he played harder. He spent money as fast as he made it. He thrust expensive presents on his friends and drinking companions. He ran up huge "delicatessen" bills. One of these "caterers" sued for $4588 which he had carelessly forgotten to pay. Then there were always those bellicose fellows in the bars who kept yelling, "So, you're Brod Crawford, the big movie tough guy!" Brod usually accommodated them, and as a result, tangled with some of the best cops and touched base at some - of the best pokies in town. "I'm a tough man to live with," he explains. "I get a wild hair up my nose and I want to go."

The wild hairs were often - just a smoke screen for the most delicate nuance of feeling. In 1940 he married actress Kay Griffith, who not only understood but loved him, which was quite a feat, considering she had to compete with Helen. "We wanted a child. Kay kept having miscarriages. So in 1947 we decided to adopt one."

Only Brod could have done it the way he did. He deliberately chose one who was "not right". The feet were deformed, the eyes were crossed, the little brain was thought to be retarded. "I said give me the worst one. He needs me more. I can make him into everything I always wanted to be."

Kim posed a cruel dilemma. While the surgeons eventually straightened out the eyes, and the retardation proved a wrong diagnosis, the club feet were something else again. The Crawfords had to decide whether to operate, which would leave him with legs like match sticks, or keep him in a cast for nine years while they straightened out naturally. Crawford chose the latter course.

"I was strong enough. I'd carry him. I'd be his sight, too. Before long I knew how lucky I was to have him. I could make him laugh. I took him to Spain with me. We had great times together. I told him, 'Kid, someday you'll be carrying me.' And he did." Pause. "I guess it's the only time I ever felt up to being Helen Broderick's son."

Still, even this was not enough to still the turmoil in him. When his movie career began to slack off, he took to TV. Highway Patrol was a simple-minded police show. To hold down boredom, Crawford did his own stunts, regularly breaking things, mostly his arm. The show shot in two days from a script that sometimes seemed to have taken half that to write. There was no break between shows and Brod was never entirely certain what show they were on. Once he started to read some simple dialogue only to have the director yell, "Cut!"

"Hey, Bred, what show yuh doing?

"32-B."

"We're shooting 31-A".

Asked why he bothered with the show, he would reply, "I'm no up-and-coming starlet. I identify with the payroll department. I've made upwards of a million bucks in the cops-and-robbers business. I'm still making it. So don't applaud. Just send me the check."

When Kay divorced him, and his 1961 series, King of Diamonds, flopped, Brod found another interest. Her name was Joan Tabor, an actress who bowled. "She rolled 189," he muses idly. "That bugged me. I kept asking, 'Why can't I?' "When he married her (the marriage lasted three years) he got off one of the more trenchant remarks of his life: "I've got her where she wants me."

Last year he and "a real dear friend" - the real dear friend was driving, says Brod - hit a wet slick and a phone pole in Syracuse, N.Y. "It taught me something," Brod is saying. "Windshields are breakable. They found me on the hood bleeding. I woke up four days later with an arm broken in five places, 47 stitches in my face, and a silicon kneecap. My friend broke a finger. The nurse said, 'Feeling better, Mr. Crawford?' I said, 'I'll have a vodka and Seven'."

So this season he is "charging around, scaring hell out of all those young interns" in The Interns - "Highway Patrol in a hospital," he calls it. It figures. If there's one thing he's good at, it's survival. He loves the show, he loves "the kids" in it; and we have executive producer Bob Claver's word that he shows up sober, ready for "this here acting."

He lives, he says, "outside Tucson," where he has "a house on five acres of cactus." No one - not even his best friends in Tucson - including the Southwestern artist Ted de Grazia, who taught him to paint, has ever seen it. His canvases often tend toward the macabre - black bodies hanging by the neck from a hanging tree. "I saw a lynching once," he says without explanation.

It is nearly noon, and the things on his mind are his two sons: Kelly (he and Kay finally had a natural son), who stands in for his father on the set and wants to be in the technical end of the business, and Kim, who at 23 is his pride and joy ("6-feet~A and can beat me to death") and his despair. Kim took off for Florida with a girl of whom Brod didn't approve, which bugs him. "Why? Because I give a fuck. If you're going to be a bum, be the biggest. If you're going to blow it, blow it big."

"With Kay I blew it. I'm what you call a deathbed Catholic. I only go to mass when somebody asks me, but when I get in trouble I call for a priest. I want to make someone walk straight, but I've left my sons nothing but wars. My father taught me the virtue of retreat. Still; eventually I may go home."

"Let me put it this way. I fear the mystery. You are born to die. The end is the beginning. The days may be awful lonesome, but the years are getting short. I've made my peace with myself. When I go I intend to go like a gentleman.' Meantime, I'll be up at 5 A.M. waiting for any son of a bitch that wants to ring me."